When we think of wine in the U.S., the names of grapes generally come to mind, such as Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot or Chardonnay. In France, home to many of the grapes grown in the U.S., there is more of a geographical orientation with most wines being named for the region where the grapes are grown.

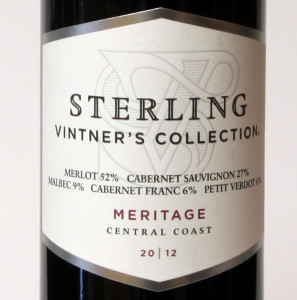

Consider Bordeaux, one of the world’s oldest and most legendary wine producing regions, highlighted in magenta on the map. There are five Bordeaux grapes: Cabernet Sauvignon, Cabernet Franc, Merlot, Petit Verdot and Malbec. In France, a Bordeaux wine is usually a combination of the two or more of these five grapes. This blending practice is occasionally used in the U.S. as well: if you stick to only the five Bordeaux grapes and pay a fee to the Meritage Society, you can label your wine a Meritage. Which, when pronounced correctly, rhymes with “heritage”.

More often, Bordeaux grapes are used in the U.S. to produce single varietals like Cabernet Sauvignon and Merlot. In practice, even if the wine label lists just one grape, it’s common to blend in something else for smoothness or character. Cabernet Sauvignon, for example, frequently contains a bit of Merlot or Cabernet Franc. Under the rules of the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms, a bottle of wine can be called a varietal if it contains at least 75% of the grape listed on the label. If the primary grape constitutes less than 75% of the wine, you must call it a Meritage, a Red Blend or a Red Table Wine.

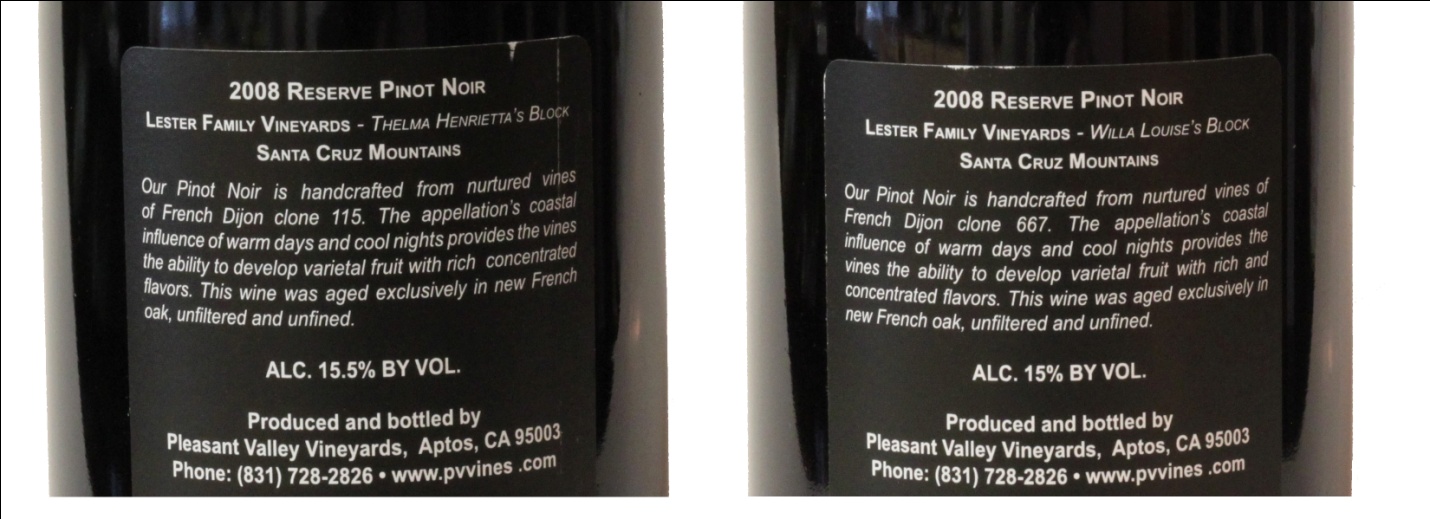

Pictured below are wines featuring four of the Bordeaux grapes: Merlot, Cabernet Sauvignon, Cabernet Franc, and Malbec. Not represented is Petit Verdot, which is rarely bottled as a single varietal, but instead is blended with other varietals to enhance the color and add tannins that improve aging.

Of the four popular Bordeaux varietals, Cabernet Sauvignon gets the most respect. Most Cabs are big, complex wines made for drinkers with an evolved palate and they can command some of the highest prices in the wine world. If you win the lottery, consider seeking out a Screaming Eagle or a Colgin Cabernet. Think I’m joking? I recently saw a 2009 Screaming Eagle Cabernet Sauvignon listed at $2095. Not for a case, not for a Jeroboam, the seller is asking $2095 for a single 750 ml bottle. If that seems a little over the top, but you want a reliably great Cab for a special occasion, consider Silver Oak’s Alexander Valley Cabernet, Sebastiani Cherryblock or something from Napa’s Stags Leap District. Better yet, go French and try a Premier Cru like Chateau Margaux or Chateau Lafite.

Merlot, on the other hand, has a reputation among critics for being a “beginner’s wine” with many producers avoiding bold flavors and tannins that might be off putting to someone unaccustomed to red wine. Paul Giamatti’s rant about his disdain for Merlot in the film Sideways didn’t help the grapes reputation, either. But in some cases, this reputation of mediocrity is undeserved. The Robert Sinskey Carneros Merlot seen in the photo is a fabulous wine, with complex flavors, a great balance and a beautiful finish.

Malbec has become popular in the U.S. in recent years, mostly owing to a dearth of excellent and affordable imports from the Mendoza region of Argentina. Cabernet Franc, like Petit Verdot, appears more often in blends than as a single varietal, but if you see a Cab Franc on the tasting menu at a winery give it go; it can be a real treat.

Stay tuned for our next post where we explore the wines of Burgundy.